To preach is to speak prophetically to the present moment. That’s not easy to do. We pastors are expected to read, understand, and interpret the Scriptures in conversation with world we’re facing, and then to tell everyone about it while proposing a plan of action. I think you’ll all agree that rightly handling the word of God is no walk in the park, but I think it’s also worth saying just how difficult it is to speak to the present moment, even if you have a grasp of the Scriptures.

A conversation with my good friend Matt Van Winkle has gotten me thinking about this. As I see it, the difficulty is two-fold.

First, it’s not easy to know what the “present moment” is. Are we talking politics? The social moment? The historical epoch? The reigning cultural nous? There are competing ideas of what the defining issues of our day are, and pastors feel the constant pressure to agree, disagree, define, and redefine what’s at stake.

The second problem—and this is what Matt highlighted—is the question of who our audience is as the church. Are we talking to the church, to our society, or to both? As Matt pointed out, Paul is insistent in 1 Corinthians 5 that it’s not the church’s job to judge the world. His concern—and his advice to the Corinthians—is to judge the church. “Purge the evil person from among you,” he says, for what have we to do with outsiders (vv. 12-13)?

Preaching will inevitably and always imply certain things about the world. In the same passage, Paul calls non-Christians sexually immoral, greedy idolaters. But that’s somewhat incidental to his concern to rid the church of its evil. Paul’s also living in a world where those outside of the church don’t care what he thinks about them. Does American society care what, say, my fellowship (the Assemblies of God) thinks about it? I’m not sure, but either way there’s a risk that the church can so preoccupy itself with speaking to society that it forgets itself.

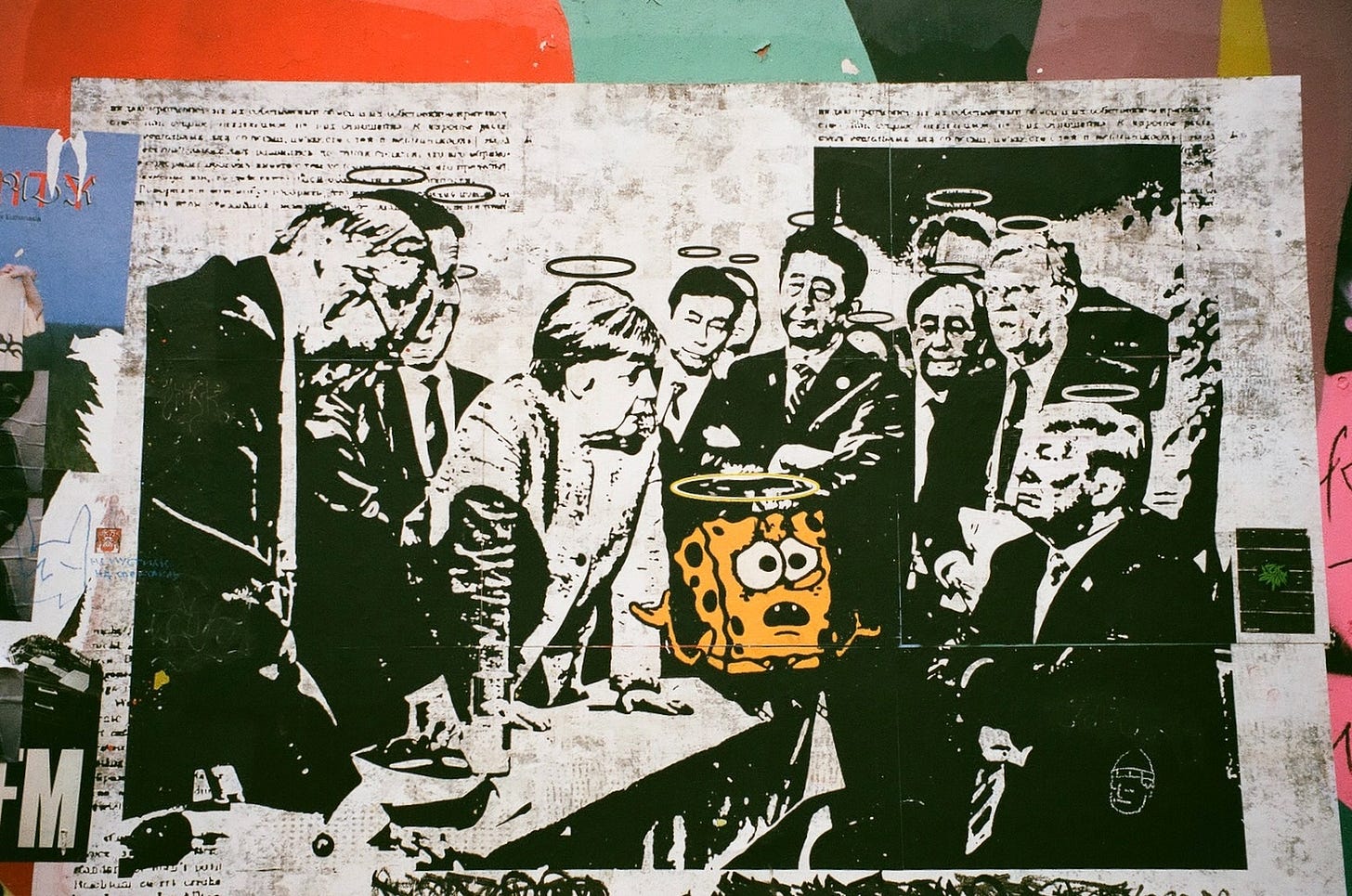

Still, I think the risk also runs in the opposite direction, where the church is silent against societal evil. The pre-war German church is often referenced in this respect. Biblically, it’s worth remembering that while Paul’s first concern was the church, he also confronted kings and magistrates, and he sought an audience with Caesar in Rome. John the Baptist called out Herod. And John’s apocalyptic visions don’t take it easy on the empire of the beasts.

So what is the prophetic task of the church? And who should we be speaking to? Here are some guidelines that give no easy answers:

Preachers (and all Christians) need to be humble, curious, and bold interpreters of society and the world. We need to ask questions like, “What does the porn industry have to do with the inordinate amount of money the United State spends on its military?” And, “What do skyrocketing suicide rates have to do with Black Friday?” I think all of those things are related, just as John of Revelation was sure that the Whore of Babylon had everything to do with the Beast that Rises from the Sea. If you’re only getting your societal, political, and cultural analysis from the news and/or social media, you’re not going to ask these questions, nor are you going to be able to venture intelligent (let alone prophetic) answers.

(I will add here that biblical illiteracy begets cultural illiteracy. We’ve ceased to be humble, curious, and bold interpreters of the Bible, and that’s bled into all of life).

We’re not called to nation building. America is not the church’s project. America can fail, and the church will go on. We’ve all heard pastors parrot news pundits who claim that every successive presidential election is the most important in American history. That sort of rhetoric fixes our gaze on the supposed decline of the nation rather than on the alarming decline of the church in the West. It’s time for us to remember, preach, and pray what our Lord told us to pray—that his kingdom would come. As often as we pray it, we are praying for the end of America and the fullness of the kingdom. Let that sink in.

Christians must take a stand for the common good. (Which means we’re not actively trying to end America). As I already said about defining the present moment, we also have to have some idea of what the common good is. Jesus’s restoration of the soldier’s ear might say something to us about advocating for affordable and accessible emergency healthcare. Paul’s preservation of his pagan overlords in the shipwreck might say something to us about the preservation of life more generally. And so on. Worshipping the Lord of life who flourishes eternally will inevitably mean we want to see life flourishing everywhere and all the time.

Finally, we must tune our ears to hear what the Spirit is saying. This, too, is no easy task. We can all hear voices in our head. I do all the time, which is why I’m always timid to say the Spirit has spoken until one or two others confirm it. Hearing the Spirit takes a lot of practice in prayer. It takes intimacy with the Scriptures. It means not turning God into an idol (and the only sure way to do that is to admit we routinely turn God into an idol). And it takes the whole church. The Spirit speaks to God’s people, not to individuals, which is why Jesus said there must be two or three gathered. (Note: I’m not saying that God doesn’t speak to you, I’m just saying you can’t be sure God’s speaking to you until you run it by the church).

It’s not easy to preach. But you know what is easy? Worship. As often as we say “Jesus is Lord” we’re saying something that is biblically true, culturally relevant, and purely doxological. So whatever the difficulty, let’s rely on the easy part and go from there.

The Lord bless you in this work. I look forward to hearing what you have to say.

Always so insightful. Thanks for this.